Advertisement

Special Report: ‘Massive’ breach exposes hundreds of new SAT questions

By Renee Dudley

BOSTON (Reuters) – Shortly after David Coleman took over as CEO in 2012, the College Board began redesigning its signature product, the SAT college entrance exam. The testing company also hired a consultancy to identify the risks associated with the monumental undertaking.

Among the red flags that consultant Gartner Inc raised in an October 2013 report: The not-for-profit College Board needed to better protect the material being developed for the new SAT.

Plans to secure the new test from leaks or theft had “not been developed” by the organization, the consultancy wrote in the report, reviewed by Reuters. At risk were thousands of items, or questions, that were being prepared for the redesigned SAT.

In 2014, employees at the New York-based College Board also raised concerns, arguing for limits on who could access items and answer keys for the revamped SAT, an email shows.

They were right to be worried.

Just months after the College Board unveiled the new SAT this March, a person with access to material for upcoming versions of the redesigned exam provided Reuters with hundreds of confidential test items. The questions and answers include 21 reading passages – each with about a dozen questions – and about 160 math problems.

Reuters doesn’t know how widely the items have circulated. The news agency has no evidence that the material has fallen into the hands of what the College Board calls “bad actors” – groups that the organization says “will lie, cheat and steal for personal gain.” But independent testing specialists briefed on the matter said the breach represents one of the most serious security lapses that’s come to light in the history of college-admissions testing.

To ensure the materials were authentic, Reuters provided copies to the College Board. In a subsequent letter to the news agency, an attorney for the College Board said publishing any of the items would have a dire impact, “destroying their value, rendering them unusable, and inflicting other injuries on the College Board and test takers.”

College Board spokeswoman Sandra Riley said in a statement that the organization was moving to contain any damage from the leak. The College Board is “taking the test forms with stolen content off of the SAT administration schedule while we continue to monitor and analyze the situation,” she said.

Riley declined to say whether those steps would involve cancelling or delaying upcoming tests. The next sitting of the SAT is October 1.

The breach is “a serious criminal matter,” Riley wrote. “A thorough investigation is ongoing, therefore our comments must be limited.” The College Board did not grant requests for interviews with CEO Coleman and other employees named in this article.

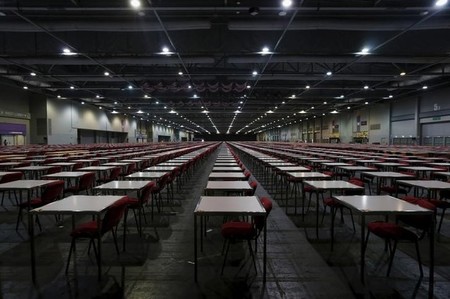

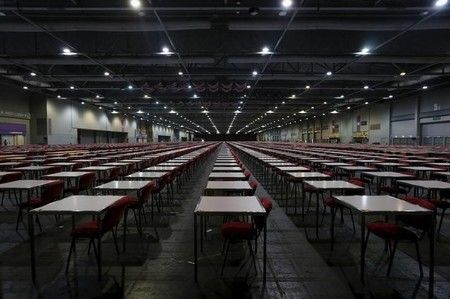

The SAT is used by U.S. universities to help evaluate more than a million college applicants a year, and so a major security lapse could cause havoc for admissions officers and students alike.

That College Board security was breached is “a problem of a massive level,” one that could “put into question the credibility of the exam,” said Neal Kingston, who heads the Achievement and Assessment Institute at the University of Kansas.

If unscrupulous test-preparation centers were to obtain the items, the impact on the SAT would be “devastating,” said James Wollack, director of the Center for Placement Testing at the University of Wisconsin.

“Everyone will pull out all stops to try to compromise this test,” Wollack said. That items for upcoming exams have leaked is “very alarming, very concerning indeed.”

It’s too soon to know what damage the leak could cause. Harm can be minimized if the items aren’t widely distributed. But Wollack and Kingston noted that the latest incident is more serious than the widespread SAT cheating reported in East Asia during the past few years.

As Reuters reported in March, the College Board has been unable to prevent foreign test-preparation operators from giving their clients an advance look at exam questions. Those problems were primarily a result of the organization’s reuse of previously administered exams. This breakdown involves test items that have never been given.

The materials provided to Reuters contain a wealth of items for upcoming tests: reading passages drawn from novels, historical documents, scientific journals, essays and other texts, each accompanied by questions. Also among the materials were math problems involving geometry and quadratic equations.

The security breach comes as the College Board already faces pressure from U.S. universities to better protect its marquee test.

The Reuters reports earlier this year detailed how an East Asian industry is exploiting the College Board’s routine practise of recycling items from past tests. Cram schools drill their students on questions harvested from previous tests, conferring an enormous advantage over students who see the items for the first time when the exam is given.

In a statement at the time, the College Board pledged to do more to protect the exam. University admissions officers, however, continue to voice concerns to College Board officials about reuse of exams. If the College Board can’t keep test material secure, schools are left with the impossible task of determining whether an applicant saw questions before taking the exam and therefore gained an unfair edge.

UNEXPLAINED LEAKS

Questions about security inside the College Board emerged earlier this year. Internal documents reviewed by this news agency showed that material for past exams had been “compromised,” a term the College Board uses to describe tests whose contents have leaked outside the organization.

In February, Reuters asked the College Board how it went about protecting exam materials. Spokesman Zach Goldberg described the organization’s use of lock boxes to help prevent the theft of SAT booklets sent to international testing locations.

But lock boxes, he acknowledged, “would not preclude a leak that originated earlier in the content development and distribution cycle.”

The question related to a confidential June 2013 PowerPoint presentation the College Board prepared after a major security breach in South Korea. After local test-prep operators obtained the test in advance, the College Board canceled the May 2013 sitting in South Korea. The PowerPoint also noted a type of breach that differed from the exploitation of recycled tests: outright leaks of new test booklets.

According to the PowerPoint, SAT tests on specialized subjects – two in Mathematics Level II and one in biology – had been compromised. These were “new forms” – that is, tests that had never been administered in the United States or abroad.

The PowerPoint gave no explanation for how those subject tests leaked. The College Board has cautioned that “cartel-like companies” in China and other countries “will stop at nothing to enrich themselves.”

EXAM INSECURITY

Historically, the development of questions to be used on the SAT was primarily handled by the non-profit Educational Testing Service, or ETS. Based in Princeton, New Jersey, ETS also oversees security for the College Board when exams are administered.

After Coleman took over, however, the College Board began handling many aspects of the SAT redesign in-house rather than through contractor ETS, documents reviewed by Reuters show. The College Board also began managing the “Item Bank,” the repository of questions created for the SAT. In the past, that responsibility had belonged to ETS.

Taking on these roles gave the College Board greater control over the material, internal documents show. Developing a single version of the SAT typically takes about 18 to 30 months and costs about $1 million.

The College Board knew that assuming those roles presented challenges.

As its staff worked on the new exam in 2013, the outside consultant was brought in to evaluate the risks the organization faced as it worked to finish the redesign.

In an internal report from October 2013 labeled “FINAL DRAFT,” Gartner advised the College Board to “develop and document a program security plan” to handle test materials. The plan should address not only the physical security of printed exam booklets, but also the safeguarding of the College Board’s network, servers, storage and data, the consultant recommended.

The security issues, the consultant concluded, presented a “medium” risk to the College Board. A “medium” risk was defined as having “a potential material impact…on program success that needs to be addressed proactively at this time.”

Risks considered “high” included the issues related to the schedule and budget for redesigning the test.

The report also recommended appointing a manager to protect the new exam. It suggested the College Board “explicitly assign a Security Lead to the Program with overall responsibility for all aspects of security related to the Assessment Redesign Program and the redesigned assessments.” Officials should “clearly document the responsibilities and mandate of this role.”

It’s unclear whether the College Board named a security chief or what steps, if any, it took to protect exam materials stored digitally. In a statement, spokeswoman Riley said the consultant later assessed how the College Board responded to the recommendations and determined “we made significant progress in every area, including our security policies and procedures.”

A spokesman for consultant Gartner declined to comment about its findings or recommendations.

An internal email shows that security concerns about access to test items remained months after the consultant’s October 2013 report.

In a June 16, 2014 email to a College Board official, test development team member Daming Zhu wrote that he and his colleagues were concerned that too many people inside College Board had “access to such secure data.” Zhu helped manage the digital repository of items being developed for the new SAT. The subject line of his email reads, “Secure Item/Test Information Sharing.”

Zhu sent the email to Sherral Miller, vice president of assessment design and development for the College Board.

Zhu’s worries were wide-ranging. “We are very concerned that IT is duplicating key information of our items and test in a parallel system,” he wrote. Another College Board unit also wanted exam information, Zhu explained. He told Miller that “storing such important secure test data in more than one place…is hard for us to understand.”

Zhu said the item bank team “believes that we ought to limit the access to the secure item/test data, especially the [answer] keys, to the minimum possible,” according to the email.

“Nowadays system hacking is not a surprise anymore,” Zhu wrote. “Expanding the sources for secure test data will not help the security of test information of high stake programs such as SAT…”

Zhu said the team “would appreciate some policies/guidelines from the department or division upper management.”

Miller replied the same day, June 16. “You are right to be leery of them at this time,” she said of the requests Zhu mentioned. Miller said she would be discussing the matter with her boss “and will then get back to you so we can set guidelines and policy.”

College Board spokeswoman Riley said the “reference to several internal inquiries to access test item information” in Zhu’s email were “potential scenarios that never manifested.” Riley said Zhu asked Miller “to confirm College Board’s policies and guidelines in order to respond to these inquiries, which Dr. Miller subsequently provided.”

Riley declined to share the guidelines, or to say how many College Board employees and contractors had access to the test items.

Testing specialists said the damage from the current breach can be limited so long as the items aren’t widely distributed. They cautioned, however, that major breaches have the potential to jeopardize the very existence of a standardized exam.

“A test like the SAT … is so important and so consequential and is taken by people all over the world,” Wollack said. The “College Board, especially for this program, needs to be leading the industry in terms of security.”

(Edited by Blake Morrison)