Advertisement

In Dallas, police serve as ‘glorified social workers’ to solve city’s ills

By Jon Herskovitz

DALLAS, August 15 (Reuters) – Antoinette Brown begged, in her final words, “somebody help me.” Then she was mauled to death by a pack of wild dogs.

The 52-year-old homeless woman perished in the impoverished Dallas neighborhood of Fair Park, not far from gleaming downtown skyscrapers and some of America’s wealthiest neighborhoods. The gruesome attack in May served as a grim reminder of stark inequities, even as the region’s economy and population booms.

The stray dog problem is just one of many facing the poorest neighborhoods of Dallas, which was labeled the “City of Hate” after the assassination of U.S. president John F. Kennedy here in 1963 and has since struggled through decades of urban blight.

Today, the mayor and others tout a host of police reforms and social programs, but they acknowledge the overwhelming challenge in bridging a racial and economic chasm with roots in the city’s segregated past. Economic inequality in Dallas, among the most severe in the U.S., has long underpinned friction between police and low-income residents here – tensions that have come into focus nationally in protests over excessive use of force.

At once such protest last month, the shooting of a dozen police officers, five of them fatally, brought a softer national spotlight on Dallas. The officers were killed by a deranged U.S. Army Reserve veteran, 25-year-old Micah X. Johnson, who said he aimed to avenge the shootings of black men by police nationwide.

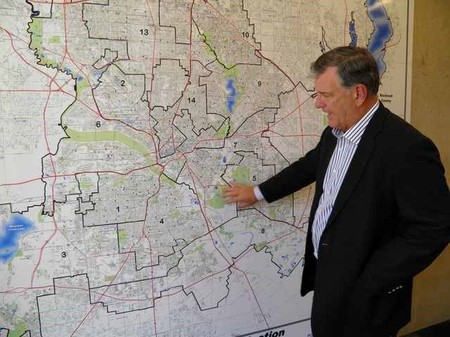

The Dallas department won praise for its handling of the protest, before and after the bloodshed, as well as a training effort credited with a drastic reduction in officer-involved shootings – to one so far this year, down from 23 in 2012. The city’s Democratic mayor, Mike Rawlings, drew attention to reforms including a plan, dubbed GrowSouth, to expand educational, employment and social opportunities in eight communities, mostly south of downtown, but including Fair Park to the east.

The goals include building low-cost housing and pushing for hotels, shops and office buildings to move into lower-income areas. There have been successes and disappointments, Rawlings told Reuters in an interview.

“I am not going to bring world peace,” the mayor said. “I am trying to establish objectives that can be achieved in a relatively short amount of time.”

LOCKED AND LOADED

The impact can be hard to see on some streets in Fair Park. Retired nurse Jametter Daniels, 65, lives about 100 yards from the abandoned house where Antoinette Brown died. Police often see the black and Latino residents of her neighborhood more as problems than people, she said, and tensions run high.

“They are just as afraid of us as we are on them,” she said from her home, with bars on the doors. “When the sun goes down, I am locked up and armed up.”

The weight of poverty, racial strife and mental illness too often lands on the weary shoulders of rank-and-file police officers, said Eugene O’Donnell, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York and a former police officer and prosecutor.

“What police have been forced to do in this country is perform triage,” he said.

In Dallas, that includes corralling potentially dangerous dogs, among other duties that extend well beyond routine crime, Dallas Police Chief David Brown told reporters last month.

“We have got a loose dog problem – let’s have the cops chase loose dogs,” he said. “Schools fail? Give it to the cops.”

Police Detective Chelsea Whitaker gets a close-up view of such failures daily.

“We can be glorified social workers,” she said.

She recalled interactions with two teenagers who constantly got into fights at school. One of them had not been eating. Whitaker took her to grocery store to buy food.

“I had to take another girl to get sanitary napkins because nobody ever taught her that,” Whitaker said of the 13-year-old. “She is angry and fighting all the time; of course, you would be angry.”

MEASURES OF POVERTY, PROGRESS

In his office overlooking downtown, Rawlings – a former Pizza Hut CEO who produced record sales – takes a corporate approach to documenting and fixing societal problems.

He has charts showing improvements in areas such as housing – where the property value of South Dallas has increased by about $1.5 billion since he took office in 2011 – and weaknesses in others, such as high unemployment rates in many neighborhoods.

Of urban areas with more than 250,000 residents, Dallas has the widest economic gap between its richest and the poorest neighborhoods, followed by Philadelphia, Baltimore, Columbus, Ohio and Houston, according to a 2015 study by the Urban Institute, a Washington D.C.-based economic social policy research organization.

South Dallas makes up about 60 percent of the city’s area and 45 percent of Dallas County’s population — yet accounts for just 15 percent of the city’s property tax base, according to the mayor’s office.

Those numbers can be read in two ways. Rawlings prefers to see the upside.

“Southern Dallas is an investment opportunity and not a charity case,” he said.

‘JOBS WITH REAL DIGNITY’

Repairing the economy of South Dallas may be beyond the ability of one well-meaning mayor, said Brianna Brown, Dallas County director for the Texas Organizing Project, a nonprofit advocating for low-income communities.

“There has been effort made that is different from other administrations,” she said. “Whether that materializes into something that is really tackling the problem – in a systemic way, with a policy solution – is a whole other question.”

Under Rawlings, the city has sought to equalize infrastructure spending – potholes, streetlights, public transportation – among rich and poor neighborhoods. The administration has also pleaded with private employers to move into poorer areas, and set up a private investment fund called Impact Dallas Capital that seeks to raise $100 million to spur investments.

Some current city efforts in low-income neighborhoods – such as regulating payday lenders and luring stores offering fresh, affordable food – are well-intentioned but difficult to execute, Brianna Brown said. The depth of the problems, she said, demand bolder reforms to the city’s education system and its economy.

“There should be jobs with real dignity,” she said.

In Fair Park, where Antoinette Brown died of dog bites, leafy parks sit next to garbage-strewn lots and unpaved roads. Keena Davis, 32, said going to an affluent neighborhood nearby, Highland Park, felt like a different world.

He wants his 12-year-old son to make the jump.

“There’s a ceiling on how high he can go, and I want him to break it,” she said. “He doesn’t deserve this neighborhood.”

(Reporting by Jon Herskovitz; Additional reporting by Marice Richter in Dallas; Editing by Brian Thevenot)