Advertisement

Wolf dens, not lone wolves, the norm in U.S. Islamic State plots

By Joseph Ax

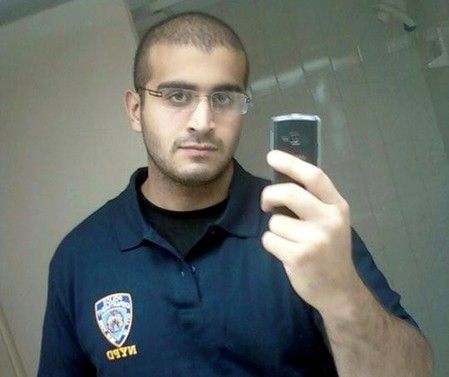

NEW YORK (Reuters) – If Omar Mateen acted alone in plotting the massacre of 49 people at Orlando’s Pulse gay nightclub, he would be the exception rather than the rule in U.S. cases involving suspected Islamic State supporters.

Sunday’s worst mass shooting in modern U.S. history prompted renewed warnings from officials of “lone wolf” attackers, a term that commonly invokes images of isolated individuals, radicalized online by violent propaganda and plotting alone.

But a Reuters review of the approximately 90 Islamic State court cases brought by the Department of Justice since 2014 found that three-quarters of those charged were alleged to be part of a group of anywhere from two to more than 10 co-conspirators who met in person to discuss their plans.

Even in those cases that did not involve in-person meetings, defendants were almost always in contact with other sympathizers, whether via text message, email or networking websites, according to court documents. Fewer than 10 cases involved someone accused of acting entirely alone.

The “lone wolf” image obscures the extent to which individuals become radicalized through personal association with like-minded people, in what might be termed “wolf dens,” experts on radicalization and counter-terrorism say.

“We focus so much on the online stuff that we’re missing that there’s a very human connection going on here,” said Karen Greenberg, who runs the Center on National Security at Fordham University in New York.

U.S. authorities on Monday were investigating whether Mateen — who pledged allegiance to Islamic State during the attack — had any help, but officials stressed they believed there were no other attackers.

FBI director James Comey said his exact motives remain unclear, but that there were strong indications he was inspired by foreign terrorist groups and that authorities were “highly confident” he was radicalized in part over the Internet.

INFILTRATING GROUPS

Law enforcement efforts to combat homegrown extremism have started to focus more on group dynamics. In a December speech at a counterterrorism conference in New York, Comey said investigators need family and friends to help them identify potentially radicalized individuals who may not have a visible online presence.

“If they go out and interact with small groups of people, who sees them?” he said. “Community members.”

In February, the FBI launched a website to educate teenagers about the dangers of extremism and help parents and community leaders decide when to intervene and when to report troubling behavior.

The Justice Department has secured convictions in around half the 90 Islamic State-linked cases. Other cases are ongoing, with some of the charges unproven in court and disputed by defendants.

The relationships between accused co-conspirators range from casual acquaintances to lifelong friends, from married couples to cousins and from roommates to college buddies.

In some cases, the group included several defendants from the same community, such as the sprawling investigation in Minnesota in which 10 Somali-Americans were charged with plotting to aid Islamic State. Three were convicted at trial this month, while six others pleaded guilty in the case.

In others, such as the married couple responsible for killing 14 people in December in San Bernardino, California, the relationship was far more intimate.

In an increasingly frequent occurrence, the defendant was unwittingly working with an FBI informant posing as a co-conspirator, as federal authorities rely more on human intelligence and less on the comparatively low-hanging fruit of social media to identify potential attackers.

Face-to-face interactions can accelerate extremist viewpoints, turning the group to violence, experts said. And it can draw in others who might otherwise not have been susceptible to the lure of jihadism.

“The true lone wolf is usually psychotic, and very few jihadists are truly psychotic,” said Jytte Klausen, a professor at Brandeis University who specializes in radicalization.

Online propaganda is merely stoking the fire rather than igniting it, some experts said.

“Imagine if Match.com were set up in such a way that the people could never meet,” said Max Abrahms, a professor at Northeastern University who has studied extremist groups. “Clearly there’s no replacement for actual socialization in person.”

“PREYING” ON INSECURITIES

One of the cases showing the crucial role of group dynamics involves a cluster of six defendants in the New York area.

Nader Saadeh and his friend, a New York City college student named Munther Omar Saleh, had become convinced in 2013 that the end of the world was near, according to prosecutors.

The two 20-year-olds decided to create a “small army” of friends, prosecutors said, and eventually recruited four others, including 21-year-old student Samuel Topaz and a 16-year-old friend of Saleh’s named Imran Rabbani.

The men spent months discussing plans to join Islamic State in Syria or to launch a bomb attack on U.S. soil, according to investigators.

Authorities first became aware of the group when Topaz’s mother called the FBI in early 2015 after becoming increasingly concerned about his behavior.

Topaz, raised by a Catholic mother from the Dominican Republic and a Jewish father from Israel, had dropped out of college and begun spending most of his time with two classmates, Saadeh and his older brother, Alaa. Topaz converted to Islam and had begun talking about traveling overseas, his mother told the FBI, according to court documents.

The Saadeh brothers were trying to recruit Topaz by “preying” on his insecurities, she said.

In May this year, Alaa Saadeh was sentenced to 15 years in prison after pleading guilty in October to conspiring to provide material support to Islamic State. His brother, Topaz and Rabbani also pleaded guilty and are awaiting sentencing.

Saleh, who is accused of plotting to set off a homemade bomb in New York, was arrested in June 2015 when he and Rabbani attacked a law enforcement surveillance vehicle that had been following them. Saleh and the other defendant, Fareed Mumuni, have pleaded not guilty.

At his sentencing, Alaa Saadeh told the judge he had acted in part out of love for his younger brother in the absence of their deported parents.

“I could have helped him,” he said. “I could have done a lot more.”

(Reporting by Joseph Ax; Additional reporting by Kristina Cooke; editing by Stuart Grudgings.)