Advertisement

Parole system questioned after murder of NBA star’s cousin

By Joseph Ax

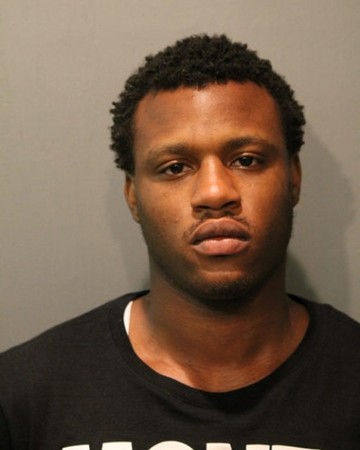

(Reuters) – Two weeks before police say Derren Sorrells and his brother murdered basketball star Dwyane Wade’s cousin in Chicago on Friday, he walked out of a state prison after serving less than four years of a six-year sentence for possessing a stolen car.

A visibly angry Eddie Johnson, the city’s police superintendent, said the case underscored the need to keep violent criminals behind bars longer.

“This reprehensible act of violence is an example of why we need to change the way we treat habitual offenders in the city of Chicago,” Johnson said on Sunday.

On Monday, Mayor Rahm Emanuel weighed in, saying, “We keep coming upon the same facts: repeat gun offenders who continually run in and out of the criminal justice system with no consequences, who are back on the streets wreaking havoc,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

Violence-plagued Chicago is not alone facing the problem of recidivism – the tendency for criminals to continue breaking the law even after being punished.

Across the United States, more than two-thirds of defendants released from state prisons were rearrested within five years, with the majority arrested within a year of release, according to a 2014 survey released by the U.S. Department of Justice.

At least 95 percent of all state prisoners will be released at some point.

Some criminal justice experts caution that limiting early release programs or imposing harsher sentences could backfire by increasing costs, straining overcrowded prisons and eliminating incentives for prisoners to behave well while incarcerated.

“It’s easy after the fact to say: ‘If I were king of the forest, I would never have let these two guys out,'” said Jeffrey Butts, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York who studies the effectiveness of criminal justice programs.

Such cases often prompt calls for tougher measures. Last fall, after a New York City police officer was killed by a convicted felon who had been admitted to a drug treatment program in lieu of prison, officials proposed stricter laws for keeping dangerous defendants behind bars.

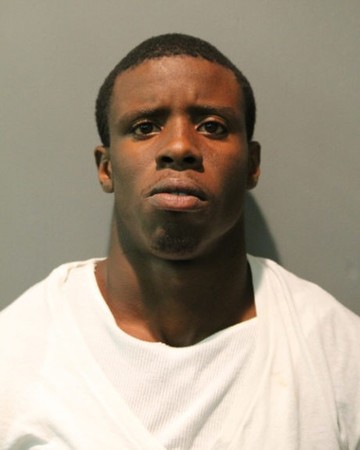

Sorrells and his brother Darwin, who was himself paroled earlier this year after serving half of a six-year sentence for gun possession, were career criminals and known gang associates, Johnson said.

Police have said the brothers were trying to shoot the driver of a vehicle when their shots struck Nykea Aldridge, who was pushing a stroller on a sidewalk. She was the cousin of Wade, the National Basketball Association star who has spoken out about gun violence in the past.

Illinois prisoners become eligible for parole after serving a certain percentage of their sentence, depending on the crime and on their behavior in prison, according to Jason Sweat, the chief legal counsel for the state parole board.

The terms of each defendant’s release are governed in part by statute and in part by the board’s own determination, he said.

Chicago has struggled with rising gang violence in recent years. In July, the Major Cities Chiefs Association, a police group, released a survey showing that murders had risen 15 percent in the first six months of 2016 compared with the year-ago period in the country’s largest cities. Chicago alone was responsible for a significant portion of that increase after reporting an approximately 50 percent spike in that time.

One high-profile case is not enough to tell whether the parole system is working, said John Pfaff, a law professor at Fordham University in New York and an expert in criminal sentencing.

“It’s very easy to identify people whom we paroled too soon,” he said. “It’s much harder to see the cases of people who we’ve locked up for too long. There’s a very strong bias in favor of being tough; the costs of being too lenient are much more obvious and shocking.”

(Reporting by Joseph Ax; Editing by Dan Grebler)