Advertisement

Missouri lawmakers pass bill to restrict viewing of police camera footage

By Eric M. Johnson

(Reuters) – Missouri lawmakers passed a bill on Tuesday to restrict the public’s access to police camera footage, nearly two years after the slaying of a black teen in a St. Louis suburb fueled demands across the country for more police accountability.

The measure would block the public from accessing footage collected by cameras worn by officers and mounted inside patrol vehicles while investigations are ongoing.

Once an investigation is over, footage would remain restricted if recorded at locations where “one would have a reasonable expectation of privacy,” such as inside schools, homes and medical facilities.

Governor Jay Nixon, a Democrat, was considering whether to sign the proposal, an aide said.

The legislation was passed almost unanimously by the state’s House of Representatives on Tuesday after winning unanimous support in the state Senate. Both chambers are Republican-led.

Police in Ferguson, Missouri, were not wearing body cameras in August 2014 when a white patrolman fatally shot unarmed black teenager Michael Brown. The incident sparked months of sometimes violent protests and demands for police reforms, including mandatory body cameras. Ferguson police use cameras now.

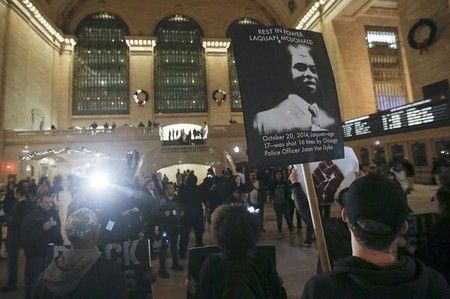

Many U.S. cities, including Los Angeles, Detroit and Seattle have also moved toward supplying patrol officers with body cameras following protests over what critics see as police use of indiscriminate force against unarmed civilians, particularly racial minorities and the mentally ill.

So far in 2016, Florida, Indiana, Utah and Washington state as well as the District of Columbia have enacted laws governing the use of body cameras, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Twenty-three states have passed laws for body cameras, the group said.

Lawmakers and the Missouri Sheriff’s Association that backed restricted access to police videos cited privacy issues, such as when officers rush into a home to help a victim of domestic violence.

While the measure restricts access to footage gathered at schools, homes and medical facilities, some people would be able to obtain copies of the recordings, including those whose images or voices are contained in the video, their attorneys or certain relatives, and insurers.

The general public including journalists would have to seek a court’s permission to access videos taken from the designated non-public places.

(Reporting by Eric M. Johnson in Seattle; Editing by Peter Cooney)