Advertisement

Disney faces PR crisis, risk of legal action after gator attack

By Lisa Richwine and Karen Freifeld

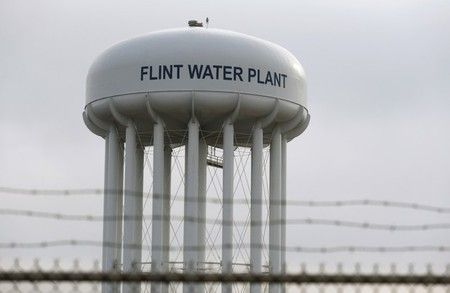

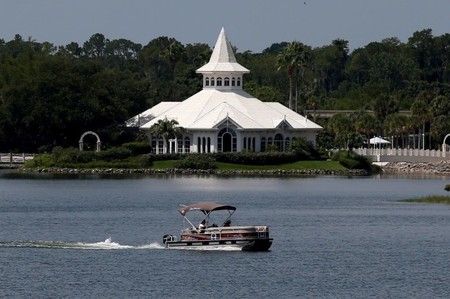

LOS ANGELES/NEW YORK (Reuters) – June was supposed to have been a triumphant month for Walt Disney Co theme parks, with the flashy opening of a long-planned resort in Shanghai and a new Florida attraction based on its wildly popular animated movie “Frozen.”

Instead, the company is facing a public relations crisis and the possibility of legal action after an alligator snatched and killed a toddler at the Walt Disney World resort in Orlando, Florida, legal and communications experts said.

“When people think of Disney they think of magic, the unbelievable, and everything is going to be fun. This incident flies in the face of that,” said Sam Singer, a crisis communications manager who represented the San Francisco Zoo after a tiger escaped and killed a teenage boy there in 2007.

The alligator tragedy unfolded on Tuesday evening, as many top Disney officials were halfway around the globe to launch the Shanghai park that had been in the works for 17 years. The company reaction was swift.

Disney Chief Executive Bob Iger called the boy’s family and publicly offered condolences. George Kalogridis, president of Walt Disney World, flew back to Florida from Shanghai. And a statement of sympathy from Kalogridis was posted on the official Disney Parks blog.

The boy’s family has not said it will file suit, saying in a public statement that they are “devastated” and thanking “local authorities and staff who worked tirelessly” after the attack.

But the possibility of a lawsuit makes Disney’s response more complicated, experts said. “The more they say, the more liability they could potentially create for themselves,” Singer said.

“They are low key, contrite and helpful,” Juda Engelmayer, a crisis manager at 5W PR, said of Disney’s response. “That’s all they can do at the moment.”

Disney plans to open its “Frozen” attraction at Epcot next week as scheduled, a spokeswoman said, though it has canceled a press event to preview the ride.

Several legal experts differed in their assessments of Disney’s potential legal liability in the attack, but most agreed the company would have a strong impetus to quickly settle any case.

They said one potential problem for the company could be that, despite creating an inviting beach environment with lounge chairs, Disney didn’t post specific warnings about alligators, instead posting “no swimming” signs.

“These people are from Nebraska and I can guarantee never once did they think they were in any type of danger letting their child wade in six inches (15 cm) of water,” said Orlando personal injury lawyer Lou Pendas, who has represented individuals in cases against Disney.

Disney plans to install new signs warning of alligators in the area, a person familiar with the matter said on Thursday.

Pendas said he could only recall one other alligator attack in the 45 years that Disney has been operating in Florida, in the 1980s when an alligator bit an eight-year-old boy, who survived.

But, Pendas said, the rarity of such attacks did not relieve Disney of responsibility.

“This is unbelievably rare but could easily have been avoided by proper signage and perhaps building a retention wall to keep the alligators off the beach,” he said. “The law says you have to take appropriate steps to keep your invitees safe.”

A Disney spokeswoman did not respond to questions about potential liability.

In a lawsuit that followed a 2009 alligator attack in which an Ohio man, James Wiencek, lost his arm while golfing at South Carolina’s Fripp Island Resort, defense lawyers argued that legal doctrine dating back to Roman times held landowners could not be held responsible for the acts of wild animals.

They also argued the danger of alligators in a coastal region of South Carolina was so well-known and obvious the golfer himself should have exercised greater care.

The case settled for an undisclosed amount before trial in 2013.

Stanford Law Professor Nora Freeman Engstrom said that Disney had a duty to protect visitors from danger and that wording and placement of the signs would be carefully looked at if the case went to trial.

The company could argue that the incident was not foreseeable and that the sign was adequate, she said. But she predicted the case would not go to trial.

“The bottom line is that they have a child whose body was snatched from the parents” as they watched, she said. “I don’t think it is the kind of case where you want to be arguing the … subtle details of law.”

(Reporting by Lisa Richwine in Los Angeles, Karen Freifeld and Anthony Lin in New York and Peter Henderson in San Francisco; Editing by Peter Henderson and Sandra Maler)