Advertisement

Closing private detention centers for migrants would pose problems: U.S. agents

By Julia Edwards

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Federal immigration agents have raised concerns about the U.S. government possibly ending its use of private detention centers used to detain undocumented migrants, a potential policy shift that some say could damage the United States’ capacity to enforce its immigration laws.

In line with a Justice Department move to phase out privately managed federal prisons, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said last month it would consider a similar change for the centers where thousands of migrants are detained, including those who have entered the country illegally and those seeking asylum or some other protected status.

There are more than 180 migrant detention centers in the United States, ranging from Pennsylvania to California, housing more than 33,000 people per day. Almost three-quarters of those detained are housed in centers that are run by or in conjunction with private contractors. (http://bit.ly/2clLZuP)

Overcrowding and impaired border security could result from closures, said recent internal memos seen by Reuters, written by agents at U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), both DHS agencies.

Debate within the DHS over the matter comes amid criticism of privately run prisons and migrant detention centers for being less safe than government-run facilities. Citing such concerns, the U.S. Department of Justice said on Aug. 18 it would phase out its use of private prisons.

That announcement hammered the stock prices of the companies that dominate the for-profit prison business. Shares of Corrections Corporation of America <CXW.N> and GEO Group Inc <GEO.N> have fallen 41 percent and 25 percent respectively since the start of this year.

Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson told an advisory council on Aug. 29 to review whether ICE should follow the Justice Department’s lead and phase out private facilities.

The Homeland Security Advisory Council is expected to make a recommendation on whether ICE should end its use of private migrant detention centers to Johnson by Nov. 30.

BIG IMPACT

The impact of such a step could be much more marked for migrant detention centers than for prisons, given that a much greater proportion of migrants are detained in private facilities.

The Justice Department’s Bureau of Prisons holds 16 percent of federal inmates in private penitentiaries, while that figure is 73 percent for migrants in detention.

As of August, there were 182 adult migrant detention facilities. Many are in the border states of Texas and Arizona, though others are in the interior of the country, in states like Indiana and Pennsylvania. Most people they hold are originally from Central America and other countries with land access to the U.S. southern border.

CBP arrests and holds migrants temporarily before they are transferred to ICE custody for a court hearing to determine whether they should be deported. CBP is not considering ending private contracts at its facilities, but some of its agents have warned of delays if ICE has less space available to take migrants.

One DHS official who asked to speak on the condition of anonymity because of the divisive nature of the topic, said ending private detention for migrants would require Congress to spend millions more dollars because government-run operations are more costly.

Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton has said she would end all private detention facilities if elected. Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has said he would enforce the U.S. border with Mexico by building a wall.

FLUCTUATING MIGRANT FLOWS

Unlike federal prisoners who may be locked up for many years, migrants are typically detained for short periods, about 27 days on average. After that, they are either deported or released to await trial.

Rehabilitation is a key goal in the prison system, but it is not a feature in migrant detention centers, an ICE official said.

Before Johnson’s announcement on private prisons, ICE had defended its decision to continue using private centers. A spokeswoman for ICE told Reuters that they allow the agency to adjust quickly to fluctuating trends in migrant flows.

For example, Corrections Corporation of America was able to build a center in Dilley, Texas, within four months in 2014 to hold Central American women and children who began coming across the border by the thousands in an unforeseen surge.

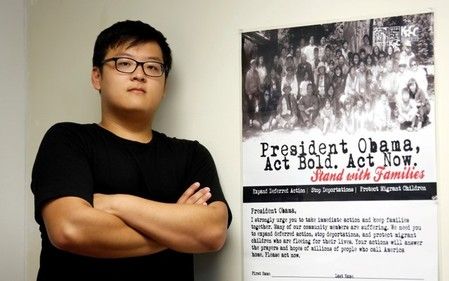

Immigrant rights advocates have criticized private detention facilities for years, saying they hold people in inhumane conditions and restrict their access to lawyers.

“Private detention facilities often hold immigrants in well-documented appalling and inhumane conditions where abuse and neglect are rampant,” said U.S. Senator Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat from Connecticut, in a statement after Johnson’s announcement.

(Editing by Kevin Drawbaugh and Bill Rigby)