Advertisement

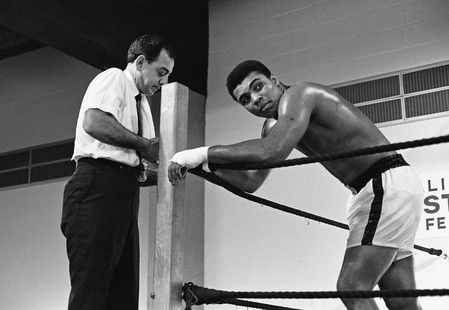

Muhammad Ali: ‘Greatest’ boxer, showman, ambassador

By Bill Trott

(Reuters) – More than 60 years ago, a bicycle thief in Louisville, Kentucky, unknowingly set in motion one of the most amazing sports careers in history.

An angry 12-year-old Cassius Clay went to a policeman on that day in 1954, vowing he would find the thief who took his bike and have his revenge. The policeman’s advice was to learn to box first so Clay, who would later change his name to Muhammad Ali, went to a gym, where he learned quite well.

He would go on to be a record-setting heavyweight champion and also much more. Ali was handsome, bold and outspoken and became a symbol for black liberation as he stood up to the U.S. government by refusing to go into the Army for religious reasons.

As one of the best-known figures of the 20th century, Ali did not believe in modesty and proclaimed himself not only “the greatest” but “the double greatest.”

He died on Friday at the age of 74 after suffering for more than three decades with Parkinson’s syndrome, which stole his physical grace and killed his loquaciousness.

Americans had never seen an athlete – or perhaps any public figure – like Ali. He was heavyweight champ a record three times between 1964 and 1978, taking part in some of the sport’s most epic bouts. He was cocky and rebellious and psyched himself up by taunting opponents and reciting original poems that predicted the round in which he would knock them out in. The audacity caused many to despise Ali but endeared him to millions.

“He talked, he was handsome, he did wonderful things,” said George Foreman, a prominent Ali rival. “If you were 16 years old and wanted to copy somebody, it had to be Ali.”

Ali’s emergence coincided with the American civil rights movement and his persona offered young blacks something they did not get from Martin Luther King and other leaders of the era.

“I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize,” Ali said. “But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me.”

Ali also had his share of fights outside the ring – against public opinion when he became a Muslim in 1964, against the U.S. government when he refused to be inducted into the Army during the Vietnam War and finally against Parkinson’s.

The one-time Christian Baptist became the most famous convert to Islam in American history when he announced he had joined the Black Muslim movement under the guidance of Malcolm X shortly after he first became champion. He eventually rejected his “white” name and became Muhammad Ali but split from Malcolm X during a power struggle within the movement.

The U.S. Army twice rejected Ali for service after measuring his IQ at 78 but eventually declared him fit for service. When he was drafted on April 28, 1967, he refused induction and the next day was stripped of his title by the World Boxing Association. In June of that year he was found guilty of draft evasion and sentenced to five years in jail.

“Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong. No Vietnamese ever called me a nigger,” Ali said in a famous off-the-cuff statement.

He never went to jail while his case was on appeal and in 1971 the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the conviction. Still, Ali’s career had been at a standstill for almost 3-1/2 years because boxing officials would not give him licenses to fight.

‘FLOAT LIKE A BUTTERFLY’

He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on Jan. 17, 1942, as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., a name shared with a 19th century slavery abolitionist. His early boxing lessons led to several Golden Gloves titles in his youth and his career took off when he won a gold medal at the 1960 Rome Olympics.

His first professional fight was a six-round decision victory on Oct. 29, 1960, against Tunney Hunsaker, whose day job was police chief in Fayetteville, West Virginia.

Despite an undefeated record, Ali was a decisive underdog 3- 1/2 years later in Miami when he faced Sonny Liston, the glowering ex-convict who was then the heavyweight champion.

Ali’s credo in the ring was “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” and his dazzling hand and foot speed confounded Liston, as it would many bigger, more powerful opponents to come. Ali became world champion when Liston did not answer the bell for the seventh round.

THE ALI-FRAZIER BATTLES

Joe Frazier became the heavyweight champion while Ali was dormant appealing against his draft conviction and, after Ali’s 1970 return to the ring, the two took part in three classic fights.

The first, billed as the “Fight of the Century” in New York in 1971, was a tremendous battle that showed Ali still possessed his skills. Frazier dropped him with a left hook in the last round and, even though Ali rose quickly, Frazier won the fight on a decision. It was Ali’s first defeat after 31 victories.

Frazier lost the title to Foreman in January 1973 but the second Ali-Frazier bout still drew enormous attention in 1974 with a 32-year-old Ali winning a unanimous decision.

Then came the “Rumble in the Jungle” match against Foreman for the heavyweight crown in Kinshasa, Zaire, on Oct. 30, 1974. Ali had a surprise ploy – a passive “rope-a-dope” strategy in which he laid back against the ropes, essentially hiding behind his arms and inviting the larger, stronger Foreman to hit him until he was too tired to hit anymore.

It paid off in the eighth round, when Ali knocked out the weary Foreman with a left-right combination.

It was one of the brightest moments of Ali’s career, confirming him as one of the greatest fighters of all time.

Ali defended his title three times in 1975 before meeting Frazier once more in October in the “Thrilla in Manila.” The bout was fought in brutal heat and Ali won when Frazier’s trainer would not allow him to go out for the final round.

On Feb. 15, 1978, a careless, lethargic Ali lost his title to little-known Leon Spinks in a 15-round decision. Seven months later, he reclaimed the title with a 15-round decision over Spinks. The victory, when Ali was four months shy of 37, came 14 years after he had won his first championship.

However, Ali, whose entourage helped him to spend several fortunes, needed money and refused to leave the sport even when it was apparent that age had sapped his talents.

He retired about a year after beating Spinks but came back in 1980 to fight former sparring mate Larry Holmes, losing a lopsided bout that was stopped after 10 rounds.

A year later, he ignored pleas to retire and lost to journeyman Trevor Berbick in the Bahamas. Then he retired for good with a record of 56 wins, including 37 knockouts, and five losses.

AFTER THE RING

Ali did not have to be in a boxing ring to command the world stage. In 1990, a few months after Iraq invaded Kuwait, Iraqi ruler Saddam Hussein held dozens of foreigners hostages in hopes of averting an invasion of his country. Ali flew to Baghdad, met Saddam and left with 14 American hostages.

A nation that once questioned his patriotism cheered loudly in 1996 when he made a surprise appearance at the Atlanta Games, stilling the Parkinson’s tremors in his hands enough to light the Olympic flame. He also took part in the opening ceremony of the London Olympics in 2012, looking frail in a wheelchair.

In November 2002 he went to Afghanistan on a goodwill visit after being appointed a U.N. “messenger of peace.”

Ali was married four times, most recently to the former Lonnie Williams, who knew him when she was a child in Louisville. He had nine children, including daughter Laila, who became a boxer.

The diagnosis of Parkinson’s syndrome, which has been linked to head trauma, came about three years after Ali retired from boxing in 1981. He helped establish the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center at a hospital in Phoenix.

(Writing and reporting by Bill Trott; Editing by Frances Kerry and Paul Tait)